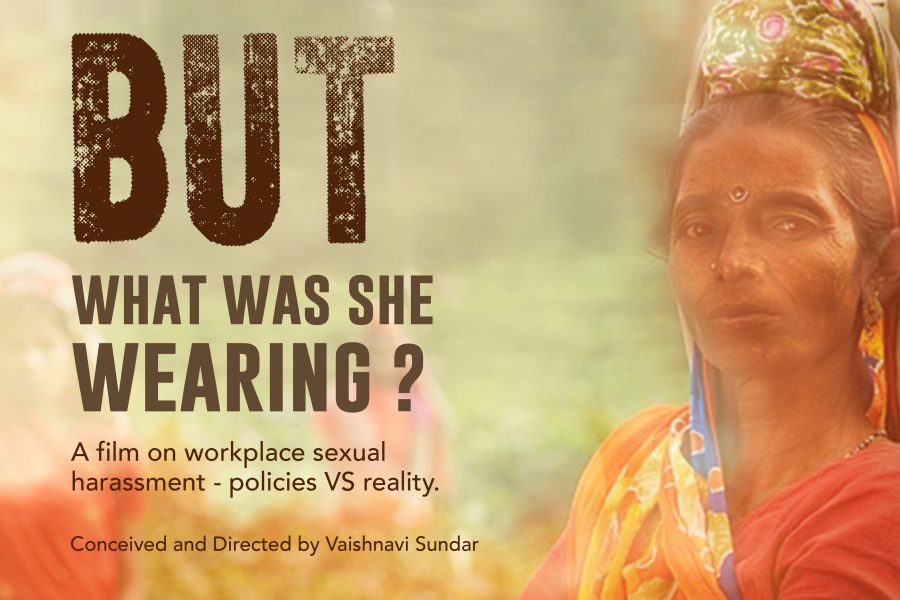

Vaishnavi Sundar’s film features several women across professions who were victims of workplace harassment, and explores the limitations of the law that was framed to address it

Chennai-based filmmaker Vaishnavi Sundar’s But What Was She Wearing? begins on a near-cynical note, from talking-head shots of women parroting the reactions of the society to cases of sexual harassment. “This is not sexual harassment. Don’t make a big deal out of it,” says one. “Stay at home. Who asked you to go out and work?” asks another. Statements that might seem curt and irrational, yet also too familiar and close to home.

Sundar’s 110-minute-long documentary is intricately-researched. It tears into the subject of workplace harassment from different angles and reveals how widespread and unchecked the problem is, and the flimsiness of the laws that are in place. The film features a horde of interviewees, cutting across classes and walks of life, who narrate personal accounts of facing and fighting sexual harassment. The film uses no visual embellishments, and sticks to the talking head style. Nevertheless, the images are powerful. The women’s courageous act of facing the camera and talking about the ordeals they went through, creates a long-lasting impact on the viewer’s mind. And there could be no better time to watch the film than now, when a second and unprecedentedly powerful wave of #MeToo is changing the narrative in urban Indian work spaces with countless women from different fields of work having come out (and still are) with names of men who sexually harassed them at work.

Merin Mathew, a former office administrator at AI SATS , recounts the sexual violence she faced at the hands of her boss, and the painful process of redressal that followed when she filed a complaint with the higher authorities although she had enough evidence against him. Suganthi P, state general secretary of All India Democratic Women’s Association of Tamil Nadu, recounts an incident where a lady cop in Madurai handed over to her a four-page letter elaborating on the sexual harassment women in the police force face in their work-space and disappeared without revealing her name, probably out of fear for life. Athira Madhav, a doctor, talks about the several incidents when she and her colleagues faced sexual harassment from patients and male colleagues in the hospital. Actress Parvathy TK speaks of the ordeal she went through during the shooting of a film where her co-star pursued her relentlessly asking for sexual favours.

“When Hannah (executive producer and intern) and I decided to explore workplace sexual harassment, we had no clue about the complexity that would unravel in front of us layer by layer,” Vaishnavi writes in her blog where she says in a tongue-in-cheek tone that the film, she hopes, ‘educates men’ and throws light on ‘the pitiable lives that women in India live’. The narrative is carefully sub-divided into categories such as Sexual Harassment At Workplace Act, Consent, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Double Victimization.

Vaishnavi spends a good amount of time in explaining the basics – the various kinds of acts that amounts to sexual harassment – since the lack of awareness about it is what aggravates the problem often, and leads the survivors to question themselves, be confused and guilty. Through the accounts of the women, the film explains that sexual harassment at workplace can sometimes be as subtle as an inappropriate conversation or double innuendo, or gestures that take women aback, like a question from the boss about breast size. One of the survivors, Merin Mathew, says that she believed sexual harassment meant rape until recently, when she studied the law to fight a case against her boss.

The film also explores how similar the struggles of working women in all sectors of job are. Activist Divya Bharathi sheds light on the wage disparity women workers face in unskilled job sectors, and how it adds to the problem of sexual harassment. Ashwini Asokan, founder and CEO of Mad Street Den, talks about the myriad prejudices that women encounter in corporate workplaces. “You are always judged – for being a woman, for being a mom; you are judged in so many different ways,” she says. This segment discusses how women often lose out on bonus or promotions for availing a rightful maternity leave. One of the notable voices is of Sharda Ugra, veteran sports journalist, who recounts how the first generation women sports reporters in India were subjected to severe gender profiling. “When they made a mistake, that story got told a thousand times,” she says.

The film analyses the most important law that is in place to tackle sexual violence at workplace, The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, that mandates the formation of an Internal Complaints Committee in every institution that employs women. The major loophole of the law is that it takes into account largely corporate workplaces, and not unorganized sector or organisations with less than ten employees. As one of the interviewees, Professor S Anandhi of Madras Institute of Development Studies says, the law consciously or unconsciously ignores the issues faced by rural women.

Also, ICC isn’t equipped to handle online sexual harassment or situations where the harassment happens to women whose job involves travelling. One of the interviewees, a researcher whose job takes her to different parts of the country, says that although she faces harassment at work, her company’s ICC doesn’t protect her as their area of jurisdiction is limited. Similarly, actors whose places of work changes from film to film, personal assistants of disabled people who often face sexual violence from family members of the person they are attending to, or domestic helpers and sanitary workers who can’t often provide enough evidence to substantiate the harassment, aren’t protected by the existing law.

The interviews also touch upon the inability of the country’s police system in helping women. The police aren’t sensitive enough to handle the cases of sexual harassment. They ask intimidating questions and make the litigants feel uncomfortable. Divya Bharathi says, “Women police stations are even worse places for women. They are completely hostile towards women who approach them with sexual harassment complaints.” Suganthi, citing the example of the woman cop who approached her for help, says, “Police stations are a place where democracy is stifled. Police women who face harassment can’t tell anyone. They have no trade unions.”

The film emphasizes the importance of family support to the survivors as sexual harassment incidents can lead to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. The interviewees also talk about cases where internal committee members landed up at the survivors’ doorstep to talk to their family, to persuade them to withdraw the case.

Recommended

The making of the film was exhausting, says Vaishnavi in her blog. For over an year, she made appeals on social media and crowd-funding platforms to fund the film that was under production, and at the end of it all, not even 70% of the film’s shoe-string budget target was met. She assumes that it’s the subject that dissuaded potential donors. “Sexual harassment is a topic that is rarely addressed and mostly misunderstood, which is why I sensed vehement resistance even within the urban “liberal” crowd,” she writes.

Now, she is looking for collaborators to screen the film in various places. “Get in touch with me if you think you can get us to screen the film in your city or if you know of a film festival that would help us leverage our work. Get in touch with us if you have stories to share, or wish to join us in the change we are desperately trying to bring about,” she appeals.

*****