A housing crisis squeezes itself through the narrative pores in Priyan Ottathilaanu, directed by Antony Sony. The sludge and the drain water from an apartment complex in Kochi clog the canal that edges a slum, leading to a clash between the two parties. The louder, less refined slum-dwellers led by a dense young man (Sudhi Koppa) against easily scared and law-abiding flat residents under the leadership of the protagonist, Priyadarshan/Priyan (Sharaf-U-Dheen), the secretary of the apartment community.

Documenting and archiving a city is one of the many accidental things a movie like this one does. Like Oruthee (2022), Priyan Ottathilaanu follows the characters as they rush through Kochi’s roads and bylanes, encountering the city’s various social and infrastructural problems. Priyan’s parents live outside the city limits, on a flood-prone terrain. His cousin, Kuttan (Biju Sopanam), a worker at a fuel station, cribs about having to live in a matchbox-sized room his employer has allotted to him. Two women, presumably poorly-paid Kudumbasree workers, slog in unhealthy conditions to fix, albeit temporarily, the building’s sewage crisis.

Antony Sony’s film is a comedy that uses these situations and people to manufacture a middle-class hero who uses the art of dialogue to solve grave practical problems. When the slum residents fume and demand that the apartment complex, which stands on what used to be a village, be demolished, Priyan urges them to talk it out. The film watches in awe as he speeds through his life, from one problem to another, never fully committing to anything yet impressing as a fruitful moderator. When his brother-in-law, a chauvinist young man resolved to harm his wife’s every attempt at getting a job and being financially independent, threatens to file for a divorce, Priyan brings the couple around a table for a discussion. “Would you not take care of him after you get a job?” he asks his sister who agrees, thus putting a lid on the marital crisis. The steep gender inequality they will, in all likeliness, continue to practise is not Priyan’s or the film’s concern. They are not worried about the pathetic conditions the slum-dwellers must be living under and the bureaucratic system that enabled this crisis either, for this is a comedy. An apolitical one at that, about circumventing issues and surviving the city rather than diving into issues and taking them head-on.

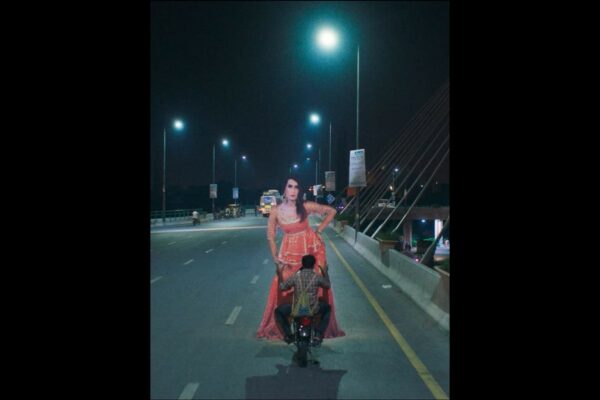

That said, the film is an effective entertainer powered by an organic sense of humour. The screenplay in a wide shot has the structure of a video game, although it is incoherent in several parts. The film follows Priyan over two days that are packed with appointments and tasks to be completed. A homoeopathic doctor, he is a closet scenarist and a moderately popular blogger. When an aspiring director approaches him to make a film out of one of his screenplays, he gladly agrees. On the given day, he must accompany the director and the movie producer (Harisree Ashokan) to meet the superstar Mammootty. Strangely, this crucial meeting that decides the project’s fate is less important in Priyan’s schedule than several menial tasks, like buying a bar of soap for his father. In the morning, at the police station where he was summoned to resolve the sewage crisis, he is entrusted with driving a stranger (Nyla Usha) to the airport. She could have just booked a taxi, but the film, like Priyan, does not adhere to common sense.

Although Antony Sony’s storytelling is old-fashioned, characterised by an excess of expository dialogue, there are a few impressive moments in the film. The apartment is introduced through the frame of a movie shooting, a scene of an abduction. A woman is being chased by a bunch of goons. When the director yells cut, the camera pulls back to reveal the residents of the apartment and the caretakers who are not so pleased with the chaos the film shooting has kicked off. Their interactions are delightfully organic and the space looks realistic. Priyan, you see, is a superhero, unusual and underrated, whose pathological inability to prioritise issues is both his superpower and vulnerability.

Sharaf-U-Dheen’s innate gentleness helps him immensely in interpreting Priyan. When he smiles under pressure or cracks jokes in unlikely situations, it does not poke out like a sore thumb. Sharaf, who can slide from a comic moment to a darker one without stiffening up his shoulders but subtly transforming himself without the onlooker noticing it, is one of the most exciting actors working in Malayalam cinema presently. An actor whose secret isn’t in his eyes or the tip of his nose, but somewhere not easily visible.

Priyan Ottathilaanu, like Antony’s debut film C/O Saira Banu, does not aspire to shake or stir the audience but appease them. It massages their lack of will to think deeply or engage with the larger society and the politics that govern it. The slapstick comedy (Jaffar Idukki and Biju Sopanam are a riot) works and the film encompasses a non-threatening heartwarming quality that could make it a weekend win at the box office. At the end of it all, the city applauds Priyan for sweeping its problems under a giant translucent carpet. A perfect representation of the state of affairs in Indian cities.

*****

This Priyan Ottathilanu review is a Silverscreen original article. It was not paid for or commissioned by anyone associated with the movie. Silverscreen.in and its writers do not have any commercial relationship with movies that are reviewed on the site.