On June 16, Doordarshan Malayalam uploaded a low-quality print of Yathrayude Anthyam (Journey Ends), a 1988 telefilm directed by KG George that had been unavailable on public domain for a long time, on its official YouTube channel. Once the word got out, the comment box flooded with words of gratitude from the audience that had watched the film on their television sets in 1988, the first time it was aired, for “taking them back home”, to their childhood.

There is a certain value that time deposits on works of art which we summarise in the word ‘nostalgia’. We stop gauging them by their face value, but through the distortions caused by the memories they evoke. Several Malayalam films post-2010 have tried to harness nostalgia’s great potential, by using images, actors and references that provoke our memories about analog era’s popular culture. Yathrayude Anthyam is George’s least discussed work, one reason being the film’s unavailability on any public domain until recently. In its sudden reappearance in the digital era, the film offers the viewers old and new a unique opportunity to navigate the past without a “moderator” as it is in the case of new films.

The film is centred on an unusual friendship, between VKV (Murali), a young writer, and Abraham (Soman), an old farmer, who meet through a series of letters, a correspondence initiated by the latter who’s a voracious reader and zestfully carried forward by the former who finds a mentor in him. The screenplay, written by George and John Paul, is based on a short story by KE Mathai aka Parappurathu, a Kerala Sahithya Akademi award-winning writer and scenarist. The majority of the film unfolds inside a moving KSRTC (Kerala State Road Transport Corporation) bus from Thiruvalla town to rural Wayanad, a journey that begins in an afternoon and ends in the next dawn. The writer is on his way to meet his friend who, on the previous evening, sent him a telegram, an SOS. The passengers who board the bus and alight at various points, contribute their bits to the narrative.

KG George, a winner of a National Film Award and multiple Kerala State Film Awards, is a principal figure in the new wave Malayalam cinema that began in the 70s. Yathrayude Anthyam has a low-key style, radically different from much of George’s filmography. One of his final films, it lies sandwiched between Mattoral (1987) and Ee Kanni Koodi (1990), films of pitch-dark shade where women’s efforts to redefine their roles in traditional family structure and free themselves of the patriarchal chains culminate in tragedy.

Yathrayude Anthyam is more fatalist in nature. The theme is transcendental, about life, death and the journey in between. George’s emphasis on technique is at its lightest here. He focuses on creating an authentic social environment for his characters. The narrative is non-linear; it links the scenes inside the bus to the many warm memories and a dream the writer slides into. Everything we come to know of the friend is through the filter of the writer’s memories.

The end of 80s was a unique threshold, just preceding the era of cable TV, internet and digital modes of communication, a time when human relationships formed and flourished through mails that involved time, human labour and patience.

Yathrayude Anthyam was one of the first set of projects directly funded by Doordarshan, India’s national broadcaster which had a monopoly in the field until 1992 when cable revolution led to the birth of a slew of TRP-driven private channels that changed the Indian audience’s viewing habits forever. The broadcaster’s revenue shot up in the 80s after it opened itself to commercial enterprises.

In 1988, to widen its regional networks and reduce its dependency on Hindi language programmes, Doordarshan started producing independent films in various regional languages. The decision was also spurred by a lack of good content. In an India Today report dated August 31, 1989, the director-general of Doordarshan, Shiv Sharma, is quoted as saying, “We had to start making commercial films. The film industry was sending us their flops.”

“Yathrayude Anthyam is a monumental work, for it reminds us that television wasn’t always about cheap productions and soap operas. In the 80s, Doordarshan was a bustling ground of fresh ideas and opportunities. At that time, many national award-winning filmmakers were commissioned to make telefilms based on literary works,” says Lijin Jose, the director of 8½ Intercuts- Life and Films of KG George (documentary, 2017). “If you take a close look at KG George’s films, you can see that he has always paid great attention to the nuances of Malayali middle-class life. In Yathrayude Anthyam, you see a wedding party, including the bride and her father, travelling to the venue of the wedding in a public bus. On the way, they sing about the economic prosperity that awaits the family as the bride, a nurse, will soon migrate to the Gulf region with her husband..”

Other significant films that came out of Doordarshan’s forge include Aparna Sen’s Picnic (1989) and Aravindan’s Marattam (1989). These films didn’t have a theatrical premiere, but aired directly on television – the earliest form of OTT releases. It was perhaps the newness of the medium and the liberty it offered that prompted George to pick Parappurathu’s short story that isn’t exactly the kind of material one would associate with the auteur.

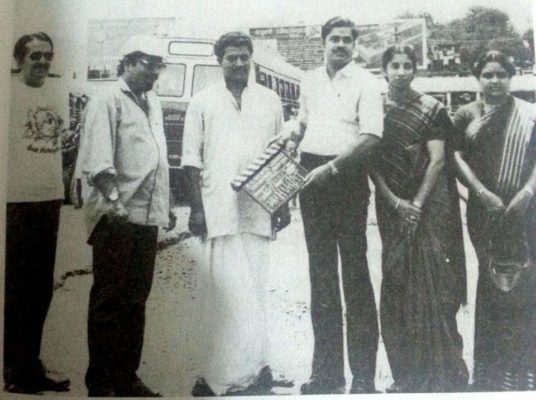

Aliyar, a veteran voice artist, actor and a professor, has fond memories of working in the film in a supporting role. He appears as a member of the wedding party led by Karamana Janardhanan Nair who plays Kunjavaran, the father of the bride, Molly (Asha Jayaram). “Most of the actors in the film, except Karamana, Asha Jayaram, Soman and Murali, were lesser-known or first time actors. Soman was one of George’s closest friends. Murali was just starting out in cinema. It was a small team,” he says. “We spent the day hours at a hotel in Thiruvalla during the night, and worked in the night. The bus where the film was shot, would ply between Thiruvalla and Mundakkayam every night…”

“The first thing I remember about the film is the chaos inside the moving bus at night. It was an exhausting shoot,” recalls cinematographer Venu who worked in the film’s first schedule. The other schedule was shot by cinematographer Sunny Joseph.

The film’s only song, an a capella, written by poet Chemmanam Chacko, falls in this portion. It has an affecting simplicity and informality. “I sang a line in the song, as a man with stutter. The one that goes “Bhagyamulla bhagyavanee Kunjavaran Chachan (Kunjavaran is a lucky man!)..” Aliyar recalls.

There are hints in the film that suggest that VKV is Parappurathu himself. There are slight references to his important work, Ara Nazhika Neram. Parappurathu uses two characters in the bus to mark his resentment at the nouveau riche Malayali who lives in the West and looks down upon the living standards back home. The only person to recognise the writer is the bus conductor who, in a charming unpretentious language, tells him of the influence his stories have had on him and his wife. Another passenger, a pompous NRI man who announces to the co-passenger several times his displeasure in travelling in a public transport in Kerala, is eager to shake hands with the writer when he comes to know that he’s famous, although, evidently, he hasn’t read anything written by him. “Writing is a severely underpaid profession in India. One must learn from the West..” he remarks, causing VKV to turn his head away in slight embarrassment.

Recommended

We learn of Abraham only through the bits and pieces of VKV’s memories. Between them, money seldom becomes a topic of conversation. They passionately discuss anthropology, history, and literature. Abraham’s worldview, shaped by his reading habits, is astonishingly modern. In one of the earlier scenes, he argues against narrow-mindedness. “We are all made up of different bloodlines. We are fossils, walking museums..” At one point, when he is talking about the pointlessness and dangers of majoritarianism, we see a church and a swastika symbol on a wall.

The sights and people VKV comes across during the bus journey start to foreshadow his destination, a graveyard where Abraham would be buried. George is now 74 and suffering from various age-related ailments. Although we don’t know what the film really meant to George, looking back now, Yathrayude Anthyam reveals a side of the auteur he had been hesitant to expose. A rejection of cynicism or an acceptance of the philosophy that life has to go on, beyond grief and death.