Jee main aata hai tere daman mein sar chhupa ke ham rote rahe from the song Tere bina zindagi se koi shikwa nahi is one of the most tender lines in Hindi film songs, in my opinion.

When love has run its stormy course and assumes a mellow form in an older age, it acquires new and unstated forms of intimacy. Companionship and empathy replace the youthful struggle of love to establish its legitimacy with relation to ego.

It is these leftovers that make up the famous song from the film Aandhi (1975), remembered usually for its mischievous and masked rendering of India’s first lady prime minister Indira Gandhi. It is not the political ploy in Aandhi that interests me, for that is the most well known and obvious aspect. But Aandhi comes to mind as a relationship of an older couple- grey haired, somewhat tired and damaged by the world. It is to Gulzar’s credit that this love is not about being not able to live without someone, for there is no complaint about an absence – no shikwa – rather it is the changed meaning of life that the absence entails.

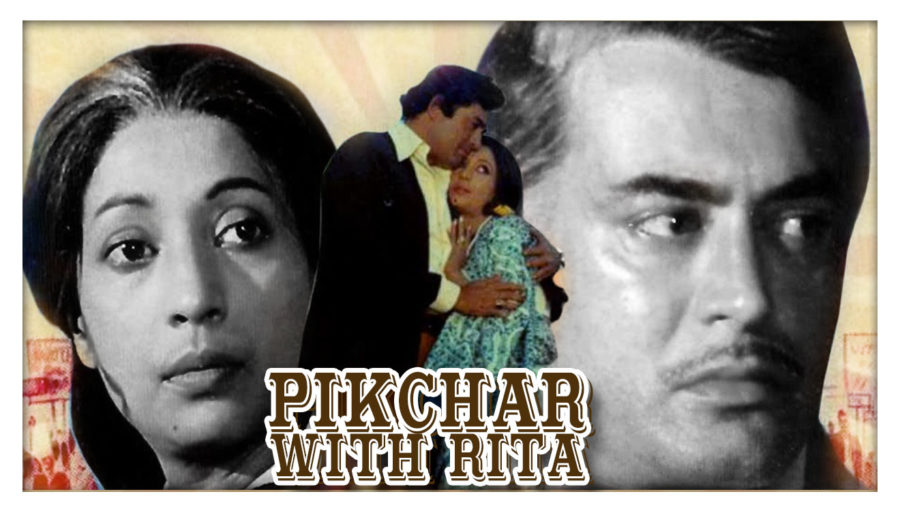

The gentle strings of the sitar, followed by the flute bring in Lata Mangeshkar at her most melodious. Unlike most songs, the visuals are understated since it’s the most accomplished pair of actors – Sanjeev Kumar and Suchitra Sen – who communicate so much through silence. This is not the age when you sing songs, but they play in your head, and it is to this interiority we are exposed. The relief to be able to cry unfettered, uncontrollably in the companionship of a gentle partner is a strange kind of desire. Or is it even desire?

Kishore Kumar’s voice as he sings Tum jo keh do to aaj ki raat chand dubega nahi is not about the male partner’s masculine strength in plucking the moon out of the sky, but of asking his partner to arrest time, extend the night, and make the stillness longer.

The same couple in their youthful days sing Tum aa gaye ho, noor aa gaya hai, nahin to chiragon se lau jaa rahi thi. If flames lose their heat and only presence brings radiance; it puts a heavy burden on being there, being with.

However, love becomes more expansive when intimacy is not about being there, but being able to cry on someone’s shoulder, of being held when long travels of life are conveyed.

A friend remarked to me, “I want to tell you things that I am not particularly proud of. But I want to be held at that time.” The intimacy of those words haunts me for it is neither sexual nor platonic, it is about being vulnerable in body and spirit.

That Sanjeev Kumar could have pulled off the role of being a husband who takes a step back to wait and watch the unfolding of political ambition and success in his wife’s life is also particularly appropriate.

The conjugality of Aandhi has more conviction even in its estrangement as tests the fundamental question of why we even need to be together.