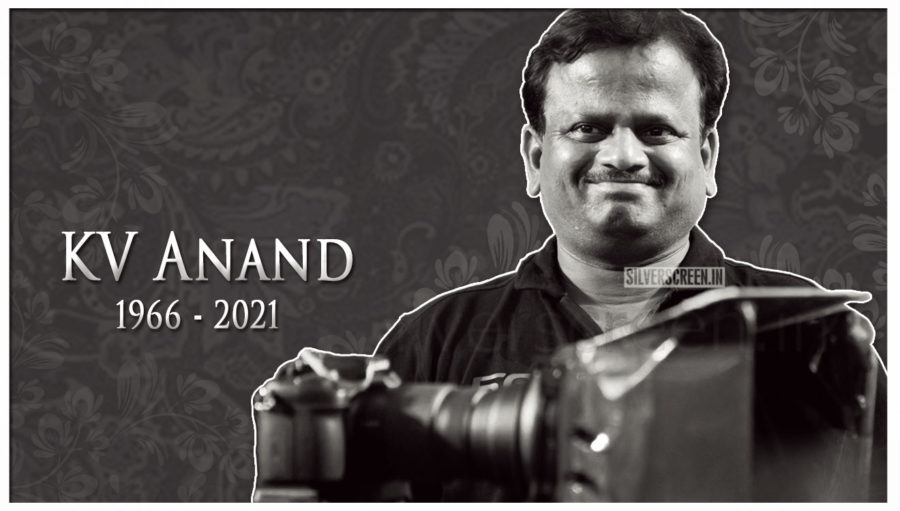

Ken Metzker, the Mumbai-based leading colourist, recalls being caught in a moment of bewilderment while working on the song Balleilakka from Sivaji: The Boss in 2007. “It was shot in vast outdoor spaces. There were groups of dancers wearing colourful costumes. You could almost see the chroma values clipping in the bright blue of the sky,” he says over the phone from Mumbai. Looking at the riot of colours on the screen, he asked the film’s cinematographer KV Anand if it wasn’t a little too much. “He smiled and told me: This song is not for technicians, but for the common people who will enjoy the show of colours without a care for a little blue clipped on the side.”

Later, when Metzker watched the film in a packed movie hall, he understood what the cinematographer meant. “KV knew the masses, which must be why he shifted to directing films for them.”

Karimanal Venkatesan Anand, the National Award-winning cinematographer and filmmaker who died on April 30 at the age of 54, was a trailblazer who pushed the boundaries of mainstream film cinematography in India.

His career as an independent cinematographer lasted 13 years in which he shot 16 films, in four languages ﹣Tamil, Telugu, Hindi and Malayalam. In 1994, he won a National Award for his debut work as an independent cinematographer ﹣director Priyadarshan’s Malayalam drama Thenmavin Kombathu. In 2005, he turned director through Kana Kandaen, a thriller. He made six more entertainers that found moderate to high commercial success.

Ironically, it was an instance of rejection that initiated him into cinema. After earning a degree in physics from a college in Chennai, he worked as a press photographer with Kalki, a Tamil-language magazine, where he shot cover photos and did a monthly photo feature titled Oru Maadham, Oru Maavattam (One Month, One District). Further, he applied for the post of photojournalist at a major news organisation. However, his application was turned down by the renowned photographer Raghu Rai who was in the recruitment panel. The resultant devastation and a flit to Andaman islands spurred in him the idea to try his luck in motion photography.

After gaining a postgraduate degree in visual communication, he joined cinematographer PC Sreeram’s team as his sixth assistant. It was Sreeram who, years later, recommended Anand’s name to director Priyadarshan who had been looking for a cinematographer for Thenmavin Kombathu.

It doesn’t take much to see why the film, shot in the pristine villages on the Kerala-Tamil Nadu border, captured the attention of the cinephiles in the country. Anand shot with little artificial lighting and no backlights except for night interiors. In a recent interview with The Hindu, Priyadarshan said, “The beautiful frames of Thenmaavin Kombathu caught the eye straight away. Pollachi had rarely looked prettier. Neither had Shobana…Balu Mahendra told me that he had never seen camera work like that before and Mani Ratnam said few outdoor sequences looked as beautiful.”

Anand and Priyadarshan collaborated on three more projects ﹣ Minnaram, Chandralekha, and Doli Saja Ke Rakhna.

Anand’s talents as a still photographer shone through the way he shot landscapes and captured the essence of places. In a Rediff interview on April 4, 1997, he spoke about discovering new places: “I can actually feel my hands trembling with excitement when I see some locale I like… there’s a realisation of the possibilities, a big thrill… it heightens when I take the camera in hand and prepare for the actual shoot… but when I get down to shooting, I find myself becoming totally calm…”

In the song Maanam Thelinje Vannaal (Thenmaavin Kombathu), he recreated the fiery colours of the desert terrain on a set constructed in South India. Kadhal Desam (1996), directed by Kathir, looked at Madras through the eyes of two teenagers. Anand imagined the city of Madras (officially renamed as Chennai in the same year) as a dreamy, sensual and young space, exploding in pop colours, neon light, music and dance. In spectacular wide shots, he captured the intimations of the city’s transition into modernity. One might agree the film’s idea of romance hasn’t aged well, but Anand’s work has withstood the test of time.

While his earlier works had the imprints of Sreeram, Anand broke the mould soon and treaded a singular path of his own. “He was not afraid to take risks or to make mistakes,” says cinematographer Richard Nathan who worked as an assistant to Anand in four films. “He was obsessed with staying abreast of every technological advancement in the field of image-making. He attempted cross-processing, a photochemical technique, in Mudhalvan (1999). He shot Khakee (2004) in Super 35mm. In those days, no one was shooting commercial films in Super 35 mm in India. He used UV lights in song sequences in Kadhal Desam and Khakee.”

Through Khakee, directed by Rajkumar Santoshi, Anand became the first Indian cinematographer to use the process of Digital Intermediate (DI), a bleeding-edge technology. The film’s peculiar colour palette was partly by design and partly, an accident. Anand and Metzker, who was then a senior colourist at Prasad EFX, Asia’s first integrated Digital Film Lab, worked for two-and-a-half months on Khakee, at once learning the new technology and finding a new visual language for the film within awful limitations.

The DI process went on for over two months. Richard remembers how Anand stood his ground and relentlessly worked on the visuals. “We made mistakes, rectified them, made mistakes again…There were disagreements and concerns within the team. The end product was imperfect, but the experience was highly enriching.”

“Back then, DI process wasn’t as streamlined or fine-tuned as it is today. There was no colour management system (CMS). Halfway through the work, we had to fly down a telecine operator from London and a representative of da Vinci colour-corrector from the USA because a lot of things were going wrong. We were on completely new grounds. Thank god, KV Anand was a man of immense patience!” Metzker recalls.

Sivaji: The Boss, directed by Shankar, another regular collaborator of Anand, had superstar Rajinikanth in the lead. There were no budget constraints or an aversion to trying out new things. Anand had to work closely with multiple departments ﹣computer graphics, make-up, DI and digital skin grafting which was used extensively in a song sequence. According to Richard, the project instilled in Anand a great sense of confidence about pulling off an out and out masala entertainer, which must have helped him in the making of his later directorial works.

Khakee forged a friendship between Metzker and Anand. “He was a good man who valued human relationships. Even in the most stressful situation, he stayed calm.” The senior colourist has fond memories of Anand taking him to the best local eateries in Madras and beating him at discovering new eateries in Mumbai. “I am yet to meet a greater food connoisseur than KV in the film industry,” he laughs.

With his assistants, Anand was a hard taskmaster. “Outside the set, he was a kind and patient mentor, but while at work, he cracked the whip. On the set, we couldn’t question him on anything. It was like being in a military training camp,” says Richard.

The greatest lesson he picked up from Anand was the importance of working against time and within the budget. “Despite Sivaji being a huge project, he did everything he could to cut the cost. He would repeat that at the end of the day, we were in business. We couldn’t afford to waste somebody else’s money. I keep this in mind while working as an independent cinematographer. I never go over budget.”

Recommended

Anand’s transition to direction didn’t produce extraordinary films. Into the framework of the mass masala genre, he inserted his social consciousness. Films such as Ko and Maattraan, which he regarded as his most satisfactory works, were shot by his assistants, Richard and Soudararajan. By his admission, he missed doing the cinematography. On social media, he generously explained the details of his work to those who sought it. He discussed still photography and new films that caught his eye.

In the star-centred ecology of the Indian film industry, his contributions as a cinematographer could get buried under the sands of time. But his experimental spirit and pervasive artistic sensitivity will not miss the eyes of those who will study the evolution of cinematography in India.