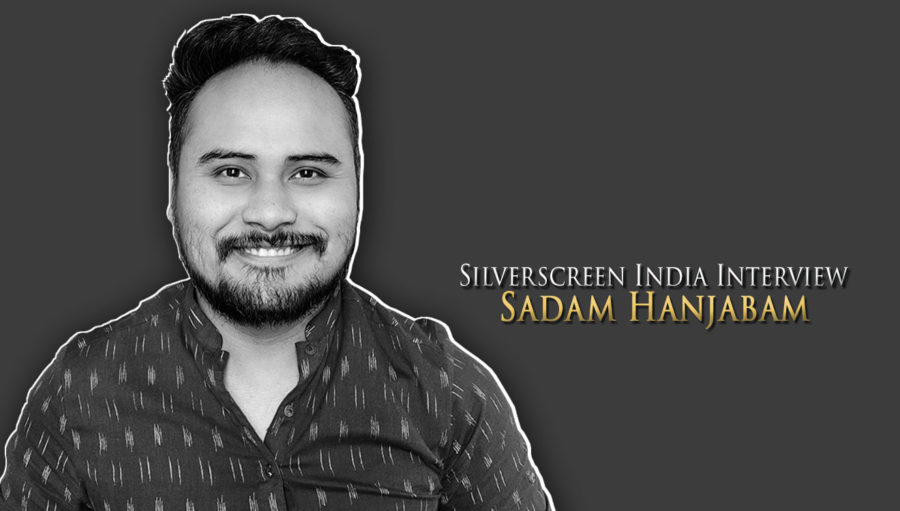

“Mental health is often stigmatised, and being queer is considered abnormal,” says Sadam Hanjabam, founder of the first registered queer and youth-led NGO in Northeast India, Ya_All.

His fight to de-stigmatise queerness and mental health in regions surrounding Manipur’s capital Imphal has caught international attention after he featured on Oprah Winfrey and Prince Harry’s Apple TV+ show The Me You Can’t See.

The six-episode series, which premiered on May 21, focuses on mental health and emotional well-being. Popular talk show host Winfrey and Prince Harry speak about their own journeys and showcase the lives of individuals from around the world, like Hanjabam, who have prioritised holistic well-being in their communities.

Speaking to Silverscreen India, Hanjabam narrates emotional and intensely personal anecdotes of coming out in a community which usually looks down on homosexuality. It was not an easy decision to leave his city to travel to the opposite end of the country to pursue an M Phil in Development Studies at Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai, he says. But it had to be done.

“I found my safe space there. Every time I returned home, I had to go back in the closet. In 2019, I decided to register an NGO called Ya_All in an effort to make my hometown Manipur a safe space for me and for others like me,” he adds.

Ya_All, which began as a collective in 2017, started by Hanjabam and his two friends, has grown since and is now registered as an NGO. The organisation provides tele-counselling support and online workshops on inclusivity in the regional language to young individuals from the queer community in Manipur. They also conduct film screenings, fashion shows and sporting events to engage the youth of the community. The NGO has capitalised on the region’s love for football and has formed the first all-trans football team in Manipur.

In a conversation with Silverscreen India, Hanjabam talks about the lack of awareness about the queer community in Manipur, recovering from addiction and depression, and establishing a helpline for his people.

What does the term ‘Queer’ mean to you?

I think of queer as solidarity. It is the term that brings the LGBTQIA+ community together.

When you registered your NGO in 2019, did you think that a big platform like The Me You Can’t See would come your way?

When we started, we just wanted to create a safe space for the LGBTQIA+ community in Manipur and the Northeast. This region has been invisible in the larger Indian queer movement. The mainland movement does not see us. Besides being shunned for our gender and sexuality, we also have our own issues of political conflict and militarization. When we began, we never thought we would reach a point where we would get to tell our story on a global platform like The Me You Can’t See. But I think this was long overdue.

How did the organisation approach you?

The communication from the show’s team came in the latter part of 2019. A crew from the United States was supposed to come down in 2020. However, things got delayed due to Covid-19. When they attempted to schedule the shoot in 2020 after restrictions eased, the crew faced visa issues. The team hence decided to have a crew from India conduct the shoot. They began shooting in November 2020 and were here for a week. We ensured Covid-19 protocols were followed while filming.

In the show, your brother features as part of your story. Did your family become more accepting after the show aired?

My brother Hanjabam Shukhdeba Sharma has been my biggest support. He understands me. I have had a conversation with my mother about my sexuality. She is over 60 years old and understands the fact that I am queer, but has not had a conversation with me about it. However, I am her child and she is hence supportive of me. This has helped me to talk freely about the topic with others.

My mother is still confused about the kind of work I do because I initially studied agriculture and am now working in the mental health space. But there is a better understanding now.

Has the show begun a larger conversation with neighbours and relatives?

It has. During the process of filming, the entire conversation got more visibility. I could come out openly with my stories. Even my friends were unable to understand my work and my sexuality earlier, but that has changed. The parents of many young children, who are part of the NGO, now understand what we do. They ask, “If Sadam’s mother and brother can accept him, then why not us?” It has become a larger conversation.

Many NGOs often view people as data. Ya_All has been looking at them from a different emotional well-being angle. This change has been visible for parents too. They have also started coming for the football practice and are supporting their kids.

How has sports helped you create a positive change in your community?

In 2017, it was difficult for us to get grants because people here — students, volunteers — did not want to connect with us through workshops. We then organised a football match in a big field in the centre of Imphal near the highway and saw passersby stop and cheer for us. It was a positive change and that is why we have continued organising a football match every year.

In our state, football tournaments are often organised in March around the time of Holi. The festival is celebrated for five days in Manipur. Every locality has sports meets for boys, girls, women, and men in different categories. There is a large-scale exclusion of queer people, particularly members of the transgender community. Most never realise that sports is so binary and discriminative. We slot one day during the festival to send a message to everyone that it’s time for queer people to be included in these celebrations.

In an article you wrote for Varta in 2019, you mentioned that not enough has been done to address the issues of the queer people in Manipur. What are the policies that the State should be focusing on? Does the government hear suggestions from NGOs like you?

The Supreme Court of India stated that trans people will be considered the third gender, but it’s just in forms. They have not provided toilets, safe space at work, schools or colleges, or proper health care in terms of therapy and transition. Trans people still have to cough up a lot of money to transition. And they have to go outside Manipur to do this, as there is no such facility in the Northeast.

Policies are made by older people who fail to consider the changes happening currently. The government does not check with us and thinks that young people are immature.

Recommended

What is your organisation looking forward to doing for the community? Will it start providing walk-in therapy soon?

We have not stopped working. Through Covid-19, we had more than 100 volunteers — all young people from Manipur — helping us out. We provided training for trans youth to do tele-counselling. We also collected Rs 20 lakh in two phases through crowdfunding and helped provide ration and healthcare to queer people in need.

Online and offline work cannot be compared. We are more comfortable offline, where we can go to schools, villages and interact with people here. But right now, we are confined to online and tele-counselling. We have five helpline numbers that are connected with the State’s helplines for mental health support. We have also resumed organising online workshops.