French-Spanish filmmaker Oliver Laxe’s third feature film, Fire Will Come, won the Uncertain Regard Jury Prize at Cannes Film Festival, 2019. In the slow-moving drama set in Laxe’s ancestral village in Spain’s Galician region, Amador (Amador Arias), a pyromaniac, returns home from prison. The film is built on images that lingers. The focus is on the inner life of the characters and the countryside where everything – human beings, animals, flora and the mountains – seems to exist in harmony. Laxe continues to use the sublime minimalist approach which has come to be his signature, although, this time, the narrative is less opaque.

The filmmaker, who was born in France and lived most of his life in Spain, moved to Morocco in his twenties, where his first two films were shot. His debut film, You All Are Captains (2010) won a FIPRESCI award at Cannes Film Festival. His sophomore feature film, Mimosas, won the Critics Week prize at Cannes in 2016.

Laxe was at the recently concluded 21st Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival where Fire Will Come was screened. After a screening and Q&A session, the 37-year-old filmmaker sat down for a chat with Silverscreen.in at the lobby of his Juhu hotel to talk about his cinematic and philosophical influences, the places he has lived in and abandoned, and the existential questions that he tries to answer through cinema.

Do you enjoy Q&A sessions?

Yes. That is why I took a long flight and came here. To talk and to listen to the audience.

Is it always possible to theorise the process of filmmaking?

I think in this case (Fire Will Come) I can because the shooting process and the end result were in sync. Everything went nearly accurate. But the case of Mimosas, my last film, was different. It was hard to do. We had no budget, that terrain (Atlas mountains) was difficult to shoot in. But in hind sight, it was a good experience. There was certainly a gap between what I wanted to achieve and what I ended up making. Yet now I feel the film I ended up making was essentially and spiritually what I really had to make. There was a call of spiritual adventure in it. It was like a prayer.

I do think this process of making films is quite mysterious. I could explain it to you for hours, but I think that the truth is something hidden and profound. I believe filmmakers are just tools of the society, time and generation. We are just a medium. The world is using us to express something. This is why I like to answer audience’s questions about how I made the film. It helps me understand my process and reasons better.

Where do your idea of images come from?

Sometimes they are within me. Sometimes I dream them. I like photographs. I enjoy watching films too. (Andrei) Tarkovsky, (Robert) Bresson… I like Apichatpong (Weerasethakul) too, although his films are a bit too dark for my taste. Most of the time, my idea of images comes from the places I visit. I feel every place holds within itself images and a soul.

You don’t use conventional narrative devices.

I believe art is an esoteric tool. But today, it is too exoteric. The hidden things – the shadows – remain hidden. There is a Sufi mystic who said, “Light is a veil.” When there is light, you see nothing. We are living in a state of decadence. I believe cinema is about the shadows. Through cinema, I am trying to explore the hidden.

In Fire Will Come, I think you can feel what is behind the exterior of things. At least, that was my intention. Today, you know, it is very difficult to make a spiritual film. The spiritual narrative is not linear or easy to understand.

There is a strong spiritual undertone in Fire Will Come. The title, which sounds like a threat or a maxim, is quite biblical. In a scene, the camera moves seamlessly from the face of human beings to the face of a cow…

I am a believer. I believe nature has rules. Nature is speaking to us all the time, and cinema has the capacity to capture that voice. I want to make images that penetrate us and heal us.

The word religion comes from the Latin word ‘religare‘ which means ‘to unite’. The world is divided. I think, as artists, our purpose is to link. To defend the fragility of the world, to protect small things and their beauty. In that sense, yes, I am religious. I pray using my camera.

But you know, in my opinion, the world is anthropocentric. I believe human beings are at the center of the equation. But that doesn’t mean that he can afford to not care about the other dimensions. He has to live in harmony. I like to shoot the face of a cow alongside the face of a human being. But at the end of the day, it’s a cow. (Smiles).

How do you choose your film’s music?

It is very intuitive. In Fire Will Come, I have used a lot of trombone music. It is a heavy metallic instrument. But it produces a sound which is aerial and very transcendent. I like that balance. I want my films to be like that. The audience should be able to smell, taste and sense things in it.

In the film, everyone in the village is sympathetic towards Almador, a prisoner on parole. There is a lot of kindness in the characters.

Yes. But I don’t think everything is perfect in the countryside. People judge each other a lot. That is why people want to escape to cities. To be anonymous. But I don’t think it is a good thing. If you hide yourself that way, your ego will be hidden from you. In a village where life is slow-moving, you will have to confront your ego.

The film opens to a nearly surreal visual of deforestation which doesn’t have an apparent connection to the rest of the film.

I call them essential images. While I was living in Morocco, I used to hear a lot about a mafia that cut palm trees at night and sold them to rich people in Casablanca. Although I had never really seen those machines cutting the trees, these images started to form inside my head. When I was writing my script, I wanted to include them in the film. Yes, the scene is not directly linked to the narrative. But I feel it completes the narrative.

The final shot of the wildfire is fascinating. It has an enigmatic sense of calmness.

In my films, you can always find a shift from human dimension to the other dimension, like a glance from the top. At first, we identify with the character whose house is burning down. We see his sadness and empathise with him. Then the camera moves upwards, detaching itself from human emotions to see the reality. It’s my way of saying that eventually, the fire will come, death will come and life will arrive after. It is a way of accepting the cycle of life. Similarly, I could have ended with the image of the son getting beaten up. But I decided to use two images of the helicopter, to give the audience a sense of distance from the human dimension.

You talk about peaceful acceptance of reality. But in life when you are shooting a film, when perhaps, funding doesn’t come on time or when production problems arise, do you accept things peacefully?

Now it’s beautiful to say that I do accept things as they come. But while shooting I don’t do that. I am trying, nevertheless. In this film, we had to finish the shoot with the actors in a real wildfire. We were shooting in the summer. In the valley, every year wildfires occur in the summer, but this time, while we were shooting there, it started raining heavily. How do you explain this? We, a crew of 15 people, waited for many days, and finally, two days before the shoot was supposed to end, there was fire.

I believe life is a test. It’s like the universe is saying, “oh you want to make a film about humble people and acceptance? Let’s see if you know what’s acceptance!”

Why did you decide to return to your ancestral village in Galicia to make a film?

I am a man of tradition. I had to come back home. I am influenced by Sufism. I visited monasteries in Senegal, Cyprus, Persia. I believe we need masters in life. It is said that if you have no master, then your ego is your master.

This village where the film is where the house of my grandparents is. You know, I was shooting on the land where several generations of my ancestors sacrificed themselves. The word sacrifice means to become sacred. They became sacred with their suffering and hard work. Shooting my film on that land, I believe, made my film is pure. Currently, I live in Galicia. I am restoring my grandparent’s house. I want to create a farm.

How are your films received in Spain?

Now, since I have prizes in Cannes, my film has an audience. We stayed in cinemas for ten days in Spain. Thirty thousand people saw it. It’s a moderate budget film compared to the mainstream films made in Spain. I started making films with my own camera, on a very small scale. Now I have a cinematographer. I really work well now.

Have you seen any Indian films?

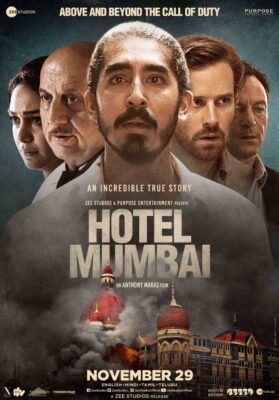

Once in Marrakesh, I happened to attend a retrospective of Indian films. I saw a Bollywood film which was directed by an important director, featuring some well-known actors. I really enjoyed it. It was very light– made for a commercial audience. But it was also very deep. It talked about destiny. I liked how it struck a balance.

Also read, ‘You Will Die At 20’ Actor Mahmoud Al-Sarraj On The Rise Of Sudanese Cinema

Read, Eeb Allay Ooo! Wins The Top Prize At 21st Jio Mami Mumbai Film Festival