In one of the first scenes in Martin Prakkat’s Nayaattu (Hunt), a police station comes alive in vivid details. The handheld camera (by cinematographer Shyju Khalid) moves dextrously from room to room, watching minuscule pieces of drama unfold at every corner. Like a factory bustling with activities, manufacturing goods for an invisible consumer, the station goes about executing the grimiest requirements of the state. The scene simmers with chaos and a sense of straight-faced detachment, setting the tone for the rest of the film.

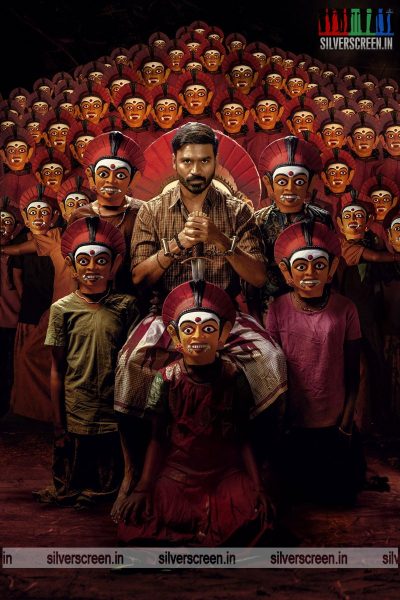

Nayaattu, written by civil police officer Shahi Kabir, looks at the state- the giant faceless authority- through the eyes of its mercenaries that ensure its efficient running. A well-crafted searing critique of the system.

The movie opens with Praveen Michael (Kunchakko Boban), a police constable merely two months into the job, being assigned to drive sub-inspector Mani (Joju George) around. During their first ride, Praveen squirms in his seat as the latter go about painting an unpleasant picture of his father in an affectionate tone. A monotonous stream of a police radio fills in the background. A scene later, Mani invites him home, treats him to ripe jackfruits and introduces him to his little daughter, as he beams with pride while taking about her.

This switching from impersonal to the personal realm, from the coldness of the system to the warmth of human connection, recurs in Nayaattu. For the constables and officers in the lower ranks, life in the police force is less lived than quietly endured. The everyday humiliation and the prick of consciousness must be quickly overlooked and moved on. The orders from the top order, regardless of their ethics, must be obeyed.

The narrative shifts gear when Mani, Praveen and a fellow constable, Sunitha (Nimisha Sajayan), are forced to flee to the unknown, fearing persecution for a crime they didn’t commit. But like animals in a zoo, they have no option but to turn around to face the master at the end.

The narrative is tightly packed, relentlessly leaping forward towards a cliff. The tragedy could be traced back to a seemingly juvenile clash of male egos, later set afire by an ugly mix of electoral politics and misogyny. The mise-en-scene is persuasive. The movie’s primary location, beside the police station featured in the initial scenes, is the long, dark road. The chief minister (Jaffer Idukki), the head of the police force and the members of a political party trying to capitalise on a friend’s accidental death sit in a place many miles away, designing an alternate truth that suits their reality.

Prakkat does not approach the film in an entire miserabilist fashion. His portrayal of the characters’ flight from their colleagues is underlined with delicate details of human survival. The interpersonal dynamics are superbly described. At a point, in the middle of nowhere the men get into a scuffle, driving Sunitha to the brink of killing herself. She, the daughter of a single mother living in a semi-concrete house in an impoverished colony, knows that she has no one to fall back on. The tumultuous scene ends in an embrace, the acknowledgement of a shared dread and hopelessness.

The police procedural part of the film is seamless, taking the viewer into the underbelly of the policies that drive the police force. A team of crime-branch officers led by an IPS officer (Yama Gilgamesh) takes over the case. Using subtle aspects ﹣like the one hard-hitting close-up shot towards the end ﹣ the film expresses the isolation and helplessness she must face in a mostly masculine force.

The film depicts the media as a mindless scavenger who creates a convenient filter for the public to see the world through. In a telling scene, the police van carrying two innocent individuals framed as criminals pass a polling station. You see a media-favourite image of a young party member helping a senior citizen cross the road and reach the booth. The camera goes back to the individuals’ bleak face, registering the cruel irony.

The film boasts an excellent cast. Joju is fantastic as Mani who, despite the self-alienating atmosphere he functions in, regards himself as a father first. Kunchakko plays Praveen with incredible restrain and beauty. An introvert with a hardened exterior, his expressions of vulnerability is brief and hesitant. Nimisha, whose career is on an excellent streak, delivers yet another powerhouse performance.

Nayaattu has a lot of things to say. In the film’s heartwrenching final sequence, the characters try to choose justice over injustice. A memory over a future. But the state, in the guise of a neatly dressed officer, sits them down and reminds them of their powerlessness. Meanwhile, at a corner of the room, a grotesque lie gets a makeover to be the truth everyone can agree with.

In Goldcoin Productions’ previous film, Ayyappanum Koshiyum, the narrative was diluted to impress the gallery and create heroes. Here, Prakkat and Kabir pick the unpleasant. Shyju Khalid’s images are unapologetically grainy. Close on the heels of an election, at the time when the film industry is clamouring for happy entertainers, Nayaattu offers to scathe and unsettle. For its finesse and forthrightness, one can’t help but take it.

****

The Nayattu review is a Silverscreen original article. It was not paid for or commissioned by anyone associated with the film. Silverscreenindia.com and its writers do not have any commercial relationship with movies that are reviewed on the site.